1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

260

261

262

263

264

265

266

267

268

269

270

271

272

273

274

275

276

277

278

279

280

281

282

283

284

285

286

287

288

289

290

291

292

293

294

295

296

297

298

299

300

301

302

303

304

305

306

307

308

309

310

311

312

313

314

315

316

317

318

319

320

321

322

323

324

325

326

327

328

329

330

331

332

333

334

335

336

337

338

339

340

341

342

343

344

345

346

347

348

349

350

351

352

353

354

355

356

357

358

359

360

361

362

363

364

365

366

367

368

369

370

371

372

373

374

|

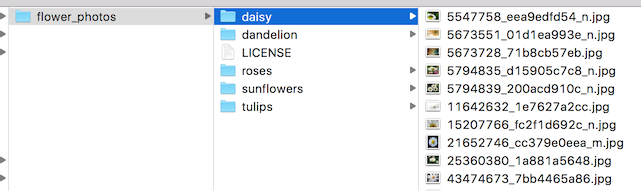

# How to Retrain Inception's Final Layer for New Categories

Modern object recognition models have millions of parameters and can take weeks

to fully train. Transfer learning is a technique that shortcuts a lot of this

work by taking a fully-trained model for a set of categories like ImageNet, and

retrains from the existing weights for new classes. In this example we'll be

retraining the final layer from scratch, while leaving all the others untouched.

For more information on the approach you can see

[this paper on Decaf](http://arxiv.org/pdf/1310.1531v1.pdf).

Though it's not as good as a full training run, this is surprisingly effective

for many applications, and can be run in as little as thirty minutes on a

laptop, without requiring a GPU. This tutorial will show you how to run the

example script on your own images, and will explain some of the options you have

to help control the training process.

Note: This version of the tutorial mainly uses bazel. A bazel free version is

also available

[as a codelab](https://codelabs.developers.google.com/codelabs/tensorflow-for-poets/#0).

[TOC]

## Training on Flowers

[Image by Kelly Sikkema](https://www.flickr.com/photos/95072945@N05/9922116524/)

Before you start any training, you'll need a set of images to teach the network

about the new classes you want to recognize. There's a later section that

explains how to prepare your own images, but to make it easy we've created an

archive of creative-commons licensed flower photos to use initially. To get the

set of flower photos, run these commands:

```sh

cd ~

curl -O http://download.tensorflow.org/example_images/flower_photos.tgz

tar xzf flower_photos.tgz

```

Once you have the images, you can build the retrainer like this, from the root

of your TensorFlow source directory:

```sh

bazel build tensorflow/examples/image_retraining:retrain

```

If you have a machine which supports

[the AVX instruction set](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Advanced_Vector_Extensions)

(common in x86 CPUs produced in the last few years) you can improve the running

speed of the retraining by building for that architecture, like this (after choosing appropriate options in `configure`):

```sh

bazel build --config opt tensorflow/examples/image_retraining:retrain

```

The retrainer can then be run like this:

```sh

bazel-bin/tensorflow/examples/image_retraining/retrain --image_dir ~/flower_photos

```

This script loads the pre-trained Inception v3 model, removes the old top layer,

and trains a new one on the flower photos you've downloaded. None of the flower

species were in the original ImageNet classes the full network was trained on.

The magic of transfer learning is that lower layers that have been trained to

distinguish between some objects can be reused for many recognition tasks

without any alteration.

## Bottlenecks

The script can take thirty minutes or more to complete, depending on the speed

of your machine. The first phase analyzes all the images on disk and calculates

the bottleneck values for each of them. 'Bottleneck' is an informal term we

often use for the layer just before the final output layer that actually does

the classification. This penultimate layer has been trained to output a set of

values that's good enough for the classifier to use to distinguish between all

the classes it's been asked to recognize. That means it has to be a meaningful

and compact summary of the images, since it has to contain enough information

for the classifier to make a good choice in a very small set of values. The

reason our final layer retraining can work on new classes is that it turns out

the kind of information needed to distinguish between all the 1,000 classes in

ImageNet is often also useful to distinguish between new kinds of objects.

Because every image is reused multiple times during training and calculating

each bottleneck takes a significant amount of time, it speeds things up to

cache these bottleneck values on disk so they don't have to be repeatedly

recalculated. By default they're stored in the `/tmp/bottleneck` directory, and

if you rerun the script they'll be reused so you don't have to wait for this

part again.

## Training

Once the bottlenecks are complete, the actual training of the top layer of the

network begins. You'll see a series of step outputs, each one showing training

accuracy, validation accuracy, and the cross entropy. The training accuracy

shows what percent of the images used in the current training batch were

labeled with the correct class. The validation accuracy is the precision on a

randomly-selected group of images from a different set. The key difference is

that the training accuracy is based on images that the network has been able

to learn from so the network can overfit to the noise in the training data. A

true measure of the performance of the network is to measure its performance on

a data set not contained in the training data -- this is measured by the

validation accuracy. If the train accuracy is high but the validation accuracy

remains low, that means the network is overfitting and memorizing particular

features in the training images that aren't helpful more generally. Cross

entropy is a loss function which gives a glimpse into how well the learning

process is progressing. The training's objective is to make the loss as small as

possible, so you can tell if the learning is working by keeping an eye on

whether the loss keeps trending downwards, ignoring the short-term noise.

By default this script will run 4,000 training steps. Each step chooses ten

images at random from the training set, finds their bottlenecks from the cache,

and feeds them into the final layer to get predictions. Those predictions are

then compared against the actual labels to update the final layer's weights

through the back-propagation process. As the process continues you should see

the reported accuracy improve, and after all the steps are done, a final test

accuracy evaluation is run on a set of images kept separate from the training

and validation pictures. This test evaluation is the best estimate of how the

trained model will perform on the classification task. You should see an

accuracy value of between 90% and 95%, though the exact value will vary from run

to run since there's randomness in the training process. This number is based on

the percent of the images in the test set that are given the correct label

after the model is fully trained.

## Visualizing the Retraining with TensorBoard

The script includes TensorBoard summaries that make it easier to understand, debug, and optimize the retraining. For example, you can visualize the graph and statistics, such as how the weights or accuracy varied during training.

To launch TensorBoard, run this command during or after retraining:

```sh

tensorboard --logdir /tmp/retrain_logs

```

Once TensorBoard is running, navigate your web browser to `localhost:6006` to view the TensorBoard.

The script will log TensorBoard summaries to `/tmp/retrain_logs` by default. You can change the directory with the `--summaries_dir` flag.

The [TensorBoard's GitHub](https://github.com/tensorflow/tensorboard) has a lot more information on TensorBoard usage, including tips & tricks, and debugging information.

## Using the Retrained Model

The script will write out a version of the Inception v3 network with a final

layer retrained to your categories to /tmp/output_graph.pb, and a text file

containing the labels to /tmp/output_labels.txt. These are both in a format that

the @{$image_recognition$C++ and Python image classification examples}

can read in, so you can start using your new model immediately. Since you've

replaced the top layer, you will need to specify the new name in the script, for

example with the flag `--output_layer=final_result` if you're using label_image.

Here's an example of how to build and run the label_image example with your

retrained graphs:

```sh

bazel build tensorflow/examples/image_retraining:label_image && \

bazel-bin/tensorflow/examples/image_retraining/label_image \

--graph=/tmp/output_graph.pb --labels=/tmp/output_labels.txt \

--output_layer=final_result:0 \

--image=$HOME/flower_photos/daisy/21652746_cc379e0eea_m.jpg

```

You should see a list of flower labels, in most cases with daisy on top

(though each retrained model may be slightly different). You can replace the

`--image` parameter with your own images to try those out, and use the C++ code

as a template to integrate with your own applications.

If you'd like to use the retrained model in your own Python program, then the

above

[`label_image` script](https://www.tensorflow.org/code/tensorflow/examples/image_retraining/label_image.py)

is a reasonable starting point.

If you find the default Inception v3 model is too large or slow for your

application, take a look at the [Other Model Architectures section](/tutorials/image_retraining#other_model_architectures)

below for options to speed up and slim down your network.

## Training on Your Own Categories

If you've managed to get the script working on the flower example images, you

can start looking at teaching it to recognize categories you care about instead.

In theory all you'll need to do is point it at a set of sub-folders, each named

after one of your categories and containing only images from that category. If

you do that and pass the root folder of the subdirectories as the argument to

`--image_dir`, the script should train just like it did for the flowers.

Here's what the folder structure of the flowers archive looks like, to give you

and example of the kind of layout the script is looking for:

In practice it may take some work to get the accuracy you want. I'll try to

guide you through some of the common problems you might encounter below.

## Creating a Set of Training Images

The first place to start is by looking at the images you've gathered, since the

most common issues we see with training come from the data that's being fed in.

For training to work well, you should gather at least a hundred photos of each

kind of object you want to recognize. The more you can gather, the better the

accuracy of your trained model is likely to be. You also need to make sure that

the photos are a good representation of what your application will actually

encounter. For example, if you take all your photos indoors against a blank wall

and your users are trying to recognize objects outdoors, you probably won't see

good results when you deploy.

Another pitfall to avoid is that the learning process will pick up on anything

that the labeled images have in common with each other, and if you're not

careful that might be something that's not useful. For example if you photograph

one kind of object in a blue room, and another in a green one, then the model

will end up basing its prediction on the background color, not the features of

the object you actually care about. To avoid this, try to take pictures in as

wide a variety of situations as you can, at different times, and with different

devices. If you want to know more about this problem, you can read about the

classic (and possibly apocryphal)

[tank recognition problem](http://www.jefftk.com/p/detecting-tanks).

You may also want to think about the categories you use. It might be worth

splitting big categories that cover a lot of different physical forms into

smaller ones that are more visually distinct. For example instead of 'vehicle'

you might use 'car', 'motorbike', and 'truck'. It's also worth thinking about

whether you have a 'closed world' or an 'open world' problem. In a closed world,

the only things you'll ever be asked to categorize are the classes of object you

know about. This might apply to a plant recognition app where you know the user

is likely to be taking a picture of a flower, so all you have to do is decide

which species. By contrast a roaming robot might see all sorts of different

things through its camera as it wanders around the world. In that case you'd

want the classifier to report if it wasn't sure what it was seeing. This can be

hard to do well, but often if you collect a large number of typical 'background'

photos with no relevant objects in them, you can add them to an extra 'unknown'

class in your image folders.

It's also worth checking to make sure that all of your images are labeled

correctly. Often user-generated tags are unreliable for our purposes, for

example using #daisy for pictures of a person named Daisy. If you go through

your images and weed out any mistakes it can do wonders for your overall

accuracy.

## Training Steps

If you're happy with your images, you can take a look at improving your results

by altering the details of the learning process. The simplest one to try is

`--how_many_training_steps`. This defaults to 4,000, but if you increase it to

8,000 it will train for twice as long. The rate of improvement in the accuracy

slows the longer you train for, and at some point will stop altogether, but you

can experiment to see when you hit that limit for your model.

## Distortions

A common way of improving the results of image training is by deforming,

cropping, or brightening the training inputs in random ways. This has the

advantage of expanding the effective size of the training data thanks to all the

possible variations of the same images, and tends to help the network learn to

cope with all the distortions that will occur in real-life uses of the

classifier. The biggest disadvantage of enabling these distortions in our script

is that the bottleneck caching is no longer useful, since input images are never

reused exactly. This means the training process takes a lot longer, so I

recommend trying this as a way of fine-tuning your model once you've got one

that you're reasonably happy with.

You enable these distortions by passing `--random_crop`, `--random_scale` and

`--random_brightness` to the script. These are all percentage values that

control how much of each of the distortions is applied to each image. It's

reasonable to start with values of 5 or 10 for each of them and then experiment

to see which of them help with your application. `--flip_left_right` will

randomly mirror half of the images horizontally, which makes sense as long as

those inversions are likely to happen in your application. For example it

wouldn't be a good idea if you were trying to recognize letters, since flipping

them destroys their meaning.

## Hyper-parameters

There are several other parameters you can try adjusting to see if they help

your results. The `--learning_rate` controls the magnitude of the updates to the

final layer during training. Intuitively if this is smaller than the learning

will take longer, but it can end up helping the overall precision. That's not

always the case though, so you need to experiment carefully to see what works

for your case. The `--train_batch_size` controls how many images are examined

during one training step, and because the learning rate is applied per batch

you'll need to reduce it if you have larger batches to get the same overall

effect.

## Training, Validation, and Testing Sets

One of the things the script does under the hood when you point it at a folder

of images is divide them up into three different sets. The largest is usually

the training set, which are all the images fed into the network during training,

with the results used to update the model's weights. You might wonder why we

don't use all the images for training? A big potential problem when we're doing

machine learning is that our model may just be memorizing irrelevant details of

the training images to come up with the right answers. For example, you could

imagine a network remembering a pattern in the background of each photo it was

shown, and using that to match labels with objects. It could produce good

results on all the images it's seen before during training, but then fail on new

images because it's not learned general characteristics of the objects, just

memorized unimportant details of the training images.

This problem is known as overfitting, and to avoid it we keep some of our data

out of the training process, so that the model can't memorize them. We then use

those images as a check to make sure that overfitting isn't occurring, since if

we see good accuracy on them it's a good sign the network isn't overfitting. The

usual split is to put 80% of the images into the main training set, keep 10%

aside to run as validation frequently during training, and then have a final 10%

that are used less often as a testing set to predict the real-world performance

of the classifier. These ratios can be controlled using the

`--testing_percentage` and `--validation_percentage` flags. In general

you should be able to leave these values at their defaults, since you won't

usually find any advantage to training to adjusting them.

Note that the script uses the image filenames (rather than a completely random

function) to divide the images among the training, validation, and test sets.

This is done to ensure that images don't get moved between training and testing

sets on different runs, since that could be a problem if images that had been

used for training a model were subsequently used in a validation set.

You might notice that the validation accuracy fluctuates among iterations. Much

of this fluctuation arises from the fact that a random subset of the validation

set is chosen for each validation accuracy measurement. The fluctuations can be

greatly reduced, at the cost of some increase in training time, by choosing

`--validation_batch_size=-1`, which uses the entire validation set for each

accuracy computation.

Once training is complete, you may find it insightful to examine misclassified

images in the test set. This can be done by adding the flag

`--print_misclassified_test_images`. This may help you get a feeling for which

types of images were most confusing for the model, and which categories were

most difficult to distinguish. For instance, you might discover that some

subtype of a particular category, or some unusual photo angle, is particularly

difficult to identify, which may encourage you to add more training images of

that subtype. Oftentimes, examining misclassified images can also point to

errors in the input data set, such as mislabeled, low-quality, or ambiguous

images. However, one should generally avoid point-fixing individual errors in

the test set, since they are likely to merely reflect more general problems in

the (much larger) training set.

## Other Model Architectures

By default the script uses a pretrained version of the Inception v3 model

architecture. This is a good place to start because it provides high accuracy

results, but if you intend to deploy your model on mobile devices or other

resource-constrained environments you may want to trade off a little accuracy

for much smaller file sizes or faster speeds. To help with that, the

[retrain.py script](https://github.com/tensorflow/tensorflow/blob/master/tensorflow/examples/image_retraining/retrain.py)

supports 32 different variations on the [Mobilenet architecture](https://research.googleblog.com/2017/06/mobilenets-open-source-models-for.html).

These are a little less precise than Inception v3, but can result in far

smaller file sizes (down to less than a megabyte) and can be many times faster

to run. To train with one of these models, pass in the `--architecture` flag,

for example:

```

python tensorflow/examples/image_retraining/retrain.py \

--image_dir ~/flower_photos --architecture mobilenet_0.25_128_quantized

```

This will create a 941KB model file in `/tmp/output_graph.pb`, with 25% of the

parameters of the full Mobilenet, taking 128x128 sized input images, and with

its weights quantized down to eight bits on disk. You can choose '1.0', '0.75',

'0.50', or '0.25' to control the number of weight parameters, and so the file

size (and to some extent the speed), '224', '192', '160', or '128' for the input

image size, with smaller sizes giving faster speeds, and an optional

'_quantized' at the end to indicate whether the file should contain 8-bit or

32-bit float weights.

The speed and size advantages come at a loss to accuracy of course, but for many

purposes this isn't critical. They can also be somewhat offset with improved

training data. For example, training with distortions allows me to get above 80%

accuracy on the flower data set even with the 0.25/128/quantized graph above.

If you're going to be using the Mobilenet models in label_image or your own

programs, you'll need to feed in an image of the specified size converted to a

float range into the 'input' tensor. Typically 24-bit images are in the range

[0,255], and you must convert them to the [-1,1] float range expected by the

model with the formula `(image - 128.)/128.`.

|