1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

260

261

262

263

264

265

266

267

268

269

270

271

272

273

274

275

276

277

278

279

280

281

282

283

284

285

286

287

288

289

290

291

292

293

294

295

296

297

298

299

300

301

302

303

304

305

306

307

308

309

310

311

312

313

314

315

316

317

318

319

320

321

322

323

324

325

326

327

328

329

330

331

332

333

334

335

336

337

338

339

340

341

342

343

344

345

346

347

348

349

350

351

352

353

354

355

356

357

358

359

360

361

362

363

364

365

366

367

368

369

370

371

372

373

374

375

376

377

378

379

380

381

382

383

384

385

386

387

388

389

390

391

392

393

394

395

396

397

398

399

400

401

402

403

404

405

406

407

408

409

410

411

412

413

414

415

416

417

418

419

420

421

422

423

424

425

426

427

428

429

430

431

432

433

434

435

436

437

438

439

440

441

442

443

444

445

446

447

448

449

450

451

452

453

454

455

456

457

458

459

460

461

462

463

464

465

466

467

468

469

470

471

472

473

474

475

476

477

478

479

480

481

482

483

484

485

486

487

488

489

490

491

492

493

494

495

496

497

498

499

500

501

502

503

504

505

506

507

508

509

510

511

512

513

514

515

516

517

518

519

520

521

522

523

524

525

526

527

528

529

530

531

532

533

534

535

536

537

538

539

540

541

542

543

544

545

546

547

548

549

550

551

552

553

554

555

556

557

558

559

560

561

562

563

564

565

566

567

568

569

570

571

572

573

574

575

576

577

578

579

580

581

582

583

584

585

586

587

588

589

590

591

592

593

594

595

596

597

598

599

600

601

602

603

604

|

# Introduction

This guide gets you started programming in the low-level TensorFlow APIs

(TensorFlow Core), showing you how to:

* Manage your own TensorFlow program (a `tf.Graph`) and TensorFlow

runtime (a `tf.Session`), instead of relying on Estimators to manage them.

* Run TensorFlow operations, using a `tf.Session`.

* Use high level components ([datasets](#datasets), [layers](#layers), and

[feature_columns](#feature_columns)) in this low level environment.

* Build your own training loop, instead of using the one

@{$premade_estimators$provided by Estimators}.

We recommend using the higher level APIs to build models when possible.

Knowing TensorFlow Core is valuable for the following reasons:

* Experimentation and debugging are both more straight forward

when you can use low level TensorFlow operations directly.

* It gives you a mental model of how things work internally when

using the higher level APIs.

## Setup

Before using this guide, @{$install$install TensorFlow}.

To get the most out of this guide, you should know the following:

* How to program in Python.

* At least a little bit about arrays.

* Ideally, something about machine learning.

Feel free to launch `python` and follow along with this walkthrough.

Run the following lines to set up your Python environment:

```python

from __future__ import absolute_import

from __future__ import division

from __future__ import print_function

import numpy as np

import tensorflow as tf

```

## Tensor Values

The central unit of data in TensorFlow is the **tensor**. A tensor consists of a

set of primitive values shaped into an array of any number of dimensions. A

tensor's **rank** is its number of dimensions, while its **shape** is a tuple

of integers specifying the array's length along each dimension. Here are some

examples of tensor values:

```python

3. # a rank 0 tensor; a scalar with shape [],

[1., 2., 3.] # a rank 1 tensor; a vector with shape [3]

[[1., 2., 3.], [4., 5., 6.]] # a rank 2 tensor; a matrix with shape [2, 3]

[[[1., 2., 3.]], [[7., 8., 9.]]] # a rank 3 tensor with shape [2, 1, 3]

```

TensorFlow uses numpy arrays to represent tensor **values**.

## TensorFlow Core Walkthrough

You might think of TensorFlow Core programs as consisting of two discrete

sections:

1. Building the computational graph (a `tf.Graph`).

2. Running the computational graph (using a `tf.Session`).

### Graph

A **computational graph** is a series of TensorFlow operations arranged into a

graph. The graph is composed of two types of objects.

* `tf.Operation` (or "ops"): The nodes of the graph.

Operations describe calculations that consume and produce tensors.

* `tf.Tensor`: The edges in the graph. These represent the values

that will flow through the graph. Most TensorFlow functions return

`tf.Tensors`.

Important: `tf.Tensors` do not have values, they are just handles to elements

in the computation graph.

Let's build a simple computational graph. The most basic operation is a

constant. The Python function that builds the operation takes a tensor value as

input. The resulting operation takes no inputs. When run, it outputs the

value that was passed to the constructor. We can create two floating point

constants `a` and `b` as follows:

```python

a = tf.constant(3.0, dtype=tf.float32)

b = tf.constant(4.0) # also tf.float32 implicitly

total = a + b

print(a)

print(b)

print(total)

```

The print statements produce:

```

Tensor("Const:0", shape=(), dtype=float32)

Tensor("Const_1:0", shape=(), dtype=float32)

Tensor("add:0", shape=(), dtype=float32)

```

Notice that printing the tensors does not output the values `3.0`, `4.0`, and

`7.0` as you might expect. The above statements only build the computation

graph. These `tf.Tensor` objects just represent the results of the operations

that will be run.

Each operation in a graph is given a unique name. This name is independent of

the names the objects are assigned to in Python. Tensors are named after the

operation that produces them followed by an output index, as in

`"add:0"` above.

### TensorBoard

TensorFlow provides a utility called TensorBoard. One of TensorBoard's many

capabilities is visualizing a computation graph. You can easily do this with

a few simple commands.

First you save the computation graph to a TensorBoard summary file as

follows:

```

writer = tf.summary.FileWriter('.')

writer.add_graph(tf.get_default_graph())

```

This will produce an `event` file in the current directory with a name in the

following format:

```

events.out.tfevents.{timestamp}.{hostname}

```

Now, in a new terminal, launch TensorBoard with the following shell command:

```bsh

tensorboard --logdir .

```

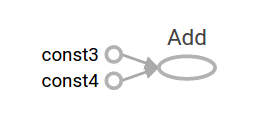

Then open TensorBoard's [graphs page](http://localhost:6006/#graphs) in your

browser, and you should see a graph similar to the following:

For more about TensorBoard's graph visualization tools see @{$graph_viz}.

### Session

To evaluate tensors, instantiate a `tf.Session` object, informally known as a

**session**. A session encapsulates the state of the TensorFlow runtime, and

runs TensorFlow operations. If a `tf.Graph` is like a `.py` file, a `tf.Session`

is like the `python` executable.

The following code creates a `tf.Session` object and then invokes its `run`

method to evaluate the `total` tensor we created above:

```python

sess = tf.Session()

print(sess.run(total))

```

When you request the output of a node with `Session.run` TensorFlow backtracks

through the graph and runs all the nodes that provide input to the requested

output node. So this prints the expected value of 7.0:

```

7.0

```

You can pass multiple tensors to `tf.Session.run`. The `run` method

transparently handles any combination of tuples or dictionaries, as in the

following example:

```python

print(sess.run({'ab':(a, b), 'total':total}))

```

which returns the results in a structure of the same layout:

``` None

{'total': 7.0, 'ab': (3.0, 4.0)}

```

During a call to `tf.Session.run` any `tf.Tensor` only has a single value.

For example, the following code calls `tf.random_uniform` to produce a

`tf.Tensor` that generates a random 3-element vector (with values in `[0,1)`):

```python

vec = tf.random_uniform(shape=(3,))

out1 = vec + 1

out2 = vec + 2

print(sess.run(vec))

print(sess.run(vec))

print(sess.run((out1, out2)))

```

The result shows a different random value on each call to `run`, but

a consistent value during a single `run` (`out1` and `out2` receive the same

random input):

```

[ 0.52917576 0.64076328 0.68353939]

[ 0.66192627 0.89126778 0.06254101]

(

array([ 1.88408756, 1.87149239, 1.84057522], dtype=float32),

array([ 2.88408756, 2.87149239, 2.84057522], dtype=float32)

)

```

Some TensorFlow functions return `tf.Operations` instead of `tf.Tensors`.

The result of calling `run` on an Operation is `None`. You run an operation

to cause a side-effect, not to retrieve a value. Examples of this include the

[initialization](#Initializing Layers), and [training](#Training) ops

demonstrated later.

### Feeding

As it stands, this graph is not especially interesting because it always

produces a constant result. A graph can be parameterized to accept external

inputs, known as **placeholders**. A **placeholder** is a promise to provide a

value later, like a function argument.

```python

x = tf.placeholder(tf.float32)

y = tf.placeholder(tf.float32)

z = x + y

```

The preceding three lines are a bit like a function in which we

define two input parameters (`x` and `y`) and then an operation on them. We can

evaluate this graph with multiple inputs by using the `feed_dict` argument of

the `tf.Session.run` method to feed concrete values to the placeholders:

```python

print(sess.run(z, feed_dict={x: 3, y: 4.5}))

print(sess.run(z, feed_dict={x: [1, 3], y: [2, 4]}))

```

This results in the following output:

```

7.5

[ 3. 7.]

```

Also note that the `feed_dict` argument can be used to overwrite any tensor in

the graph. The only difference between placeholders and other `tf.Tensors` is

that placeholders throw an error if no value is fed to them.

## Datasets

Placeholders work for simple experiments, but `tf.data` are the

preferred method of streaming data into a model.

To get a runnable `tf.Tensor` from a Dataset you must first convert it to a

`tf.data.Iterator`, and then call the Iterator's

`tf.data.Iterator.get_next` method.

The simplest way to create an Iterator is with the

`tf.data.Dataset.make_one_shot_iterator` method.

For example, in the following code the `next_item` tensor will return a row from

the `my_data` array on each `run` call:

``` python

my_data = [

[0, 1,],

[2, 3,],

[4, 5,],

[6, 7,],

]

slices = tf.data.Dataset.from_tensor_slices(my_data)

next_item = slices.make_one_shot_iterator().get_next()

```

Reaching the end of the data stream causes `Dataset` to throw an

`tf.errors.OutOfRangeError`. For example, the following code

reads the `next_item` until there is no more data to read:

``` python

while True:

try:

print(sess.run(next_item))

except tf.errors.OutOfRangeError:

break

```

If the `Dataset` depends on stateful operations you may need to

initialize the iterator before using it, as shown below:

``` python

r = tf.random_normal([10,3])

dataset = tf.data.Dataset.from_tensor_slices(r)

iterator = dataset.make_initializable_iterator()

next_row = iterator.get_next()

sess.run(iterator.initializer)

while True:

try:

print(sess.run(next_row))

except tf.errors.OutOfRangeError:

break

```

For more details on Datasets and Iterators see: @{$guide/datasets}.

## Layers

A trainable model must modify the values in the graph to get new outputs with

the same input. `tf.layers` are the preferred way to add trainable

parameters to a graph.

Layers package together both the variables and the operations that act

on them. For example a

[densely-connected layer](https://developers.google.com/machine-learning/glossary/#fully_connected_layer)

performs a weighted sum across all inputs

for each output and applies an optional

[activation function](https://developers.google.com/machine-learning/glossary/#activation_function).

The connection weights and biases are managed by the layer object.

### Creating Layers

The following code creates a `tf.layers.Dense` layer that takes a

batch of input vectors, and produces a single output value for each. To apply a

layer to an input, call the layer as if it were a function. For example:

```python

x = tf.placeholder(tf.float32, shape=[None, 3])

linear_model = tf.layers.Dense(units=1)

y = linear_model(x)

```

The layer inspects its input to determine sizes for its internal variables. So

here we must set the shape of the `x` placeholder so that the layer can

build a weight matrix of the correct size.

Now that we have defined the calculation of the output, `y`, there is one more

detail we need to take care of before we run the calculation.

### Initializing Layers

The layer contains variables that must be **initialized** before they can be

used. While it is possible to initialize variables individually, you can easily

initialize all the variables in a TensorFlow graph as follows:

```python

init = tf.global_variables_initializer()

sess.run(init)

```

Important: Calling `tf.global_variables_initializer` only

creates and returns a handle to a TensorFlow operation. That op

will initialize all the global variables when we run it with `tf.Session.run`.

Also note that this `global_variables_initializer` only initializes variables

that existed in the graph when the initializer was created. So the initializer

should be one of the last things added during graph construction.

### Executing Layers

Now that the layer is initialized, we can evaluate the `linear_model`'s output

tensor as we would any other tensor. For example, the following code:

```python

print(sess.run(y, {x: [[1, 2, 3],[4, 5, 6]]}))

```

will generate a two-element output vector such as the following:

```

[[-3.41378999]

[-9.14999008]]

```

### Layer Function shortcuts

For each layer class (like `tf.layers.Dense`) TensorFlow also supplies a

shortcut function (like `tf.layers.dense`). The only difference is that the

shortcut function versions create and run the layer in a single call. For

example, the following code is equivalent to the earlier version:

```python

x = tf.placeholder(tf.float32, shape=[None, 3])

y = tf.layers.dense(x, units=1)

init = tf.global_variables_initializer()

sess.run(init)

print(sess.run(y, {x: [[1, 2, 3], [4, 5, 6]]}))

```

While convenient, this approach allows no access to the `tf.layers.Layer`

object. This makes introspection and debugging more difficult,

and layer reuse impossible.

## Feature columns

The easiest way to experiment with feature columns is using the

`tf.feature_column.input_layer` function. This function only accepts

@{$feature_columns$dense columns} as inputs, so to view the result

of a categorical column you must wrap it in an

`tf.feature_column.indicator_column`. For example:

``` python

features = {

'sales' : [[5], [10], [8], [9]],

'department': ['sports', 'sports', 'gardening', 'gardening']}

department_column = tf.feature_column.categorical_column_with_vocabulary_list(

'department', ['sports', 'gardening'])

department_column = tf.feature_column.indicator_column(department_column)

columns = [

tf.feature_column.numeric_column('sales'),

department_column

]

inputs = tf.feature_column.input_layer(features, columns)

```

Running the `inputs` tensor will parse the `features` into a batch of vectors.

Feature columns can have internal state, like layers, so they often need to be

initialized. Categorical columns use `tf.contrib.lookup`

internally and these require a separate initialization op,

`tf.tables_initializer`.

``` python

var_init = tf.global_variables_initializer()

table_init = tf.tables_initializer()

sess = tf.Session()

sess.run((var_init, table_init))

```

Once the internal state has been initialized you can run `inputs` like any

other `tf.Tensor`:

```python

print(sess.run(inputs))

```

This shows how the feature columns have packed the input vectors, with the

one-hot "department" as the first two indices and "sales" as the third.

```None

[[ 1. 0. 5.]

[ 1. 0. 10.]

[ 0. 1. 8.]

[ 0. 1. 9.]]

```

## Training

Now that you're familiar with the basics of core TensorFlow, let's train a

small regression model manually.

### Define the data

First let's define some inputs, `x`, and the expected output for each input,

`y_true`:

```python

x = tf.constant([[1], [2], [3], [4]], dtype=tf.float32)

y_true = tf.constant([[0], [-1], [-2], [-3]], dtype=tf.float32)

```

### Define the model

Next, build a simple linear model, with 1 output:

``` python

linear_model = tf.layers.Dense(units=1)

y_pred = linear_model(x)

```

You can evaluate the predictions as follows:

``` python

sess = tf.Session()

init = tf.global_variables_initializer()

sess.run(init)

print(sess.run(y_pred))

```

The model hasn't yet been trained, so the four "predicted" values aren't very

good. Here's what we got; your own output will almost certainly differ:

``` None

[[ 0.02631879]

[ 0.05263758]

[ 0.07895637]

[ 0.10527515]]

```

### Loss

To optimize a model, you first need to define the loss. We'll use the mean

square error, a standard loss for regression problems.

While you could do this manually with lower level math operations,

the `tf.losses` module provides a set of common loss functions. You can use it

to calculate the mean square error as follows:

``` python

loss = tf.losses.mean_squared_error(labels=y_true, predictions=y_pred)

print(sess.run(loss))

```

This will produce a loss value, something like:

``` None

2.23962

```

### Training

TensorFlow provides

[**optimizers**](https://developers.google.com/machine-learning/glossary/#optimizer)

implementing standard optimization algorithms. These are implemented as

sub-classes of `tf.train.Optimizer`. They incrementally change each

variable in order to minimize the loss. The simplest optimization algorithm is

[**gradient descent**](https://developers.google.com/machine-learning/glossary/#gradient_descent),

implemented by `tf.train.GradientDescentOptimizer`. It modifies each

variable according to the magnitude of the derivative of loss with respect to

that variable. For example:

```python

optimizer = tf.train.GradientDescentOptimizer(0.01)

train = optimizer.minimize(loss)

```

This code builds all the graph components necessary for the optimization, and

returns a training operation. When run, the training op will update variables

in the graph. You might run it as follows:

```python

for i in range(100):

_, loss_value = sess.run((train, loss))

print(loss_value)

```

Since `train` is an op, not a tensor, it doesn't return a value when run.

To see the progression of the loss during training, we run the loss tensor at

the same time, producing output like the following:

``` None

1.35659

1.00412

0.759167

0.588829

0.470264

0.387626

0.329918

0.289511

0.261112

0.241046

...

```

### Complete program

```python

x = tf.constant([[1], [2], [3], [4]], dtype=tf.float32)

y_true = tf.constant([[0], [-1], [-2], [-3]], dtype=tf.float32)

linear_model = tf.layers.Dense(units=1)

y_pred = linear_model(x)

loss = tf.losses.mean_squared_error(labels=y_true, predictions=y_pred)

optimizer = tf.train.GradientDescentOptimizer(0.01)

train = optimizer.minimize(loss)

init = tf.global_variables_initializer()

sess = tf.Session()

sess.run(init)

for i in range(100):

_, loss_value = sess.run((train, loss))

print(loss_value)

print(sess.run(y_pred))

```

## Next steps

To learn more about building models with TensorFlow consider the following:

* @{$custom_estimators$Custom Estimators}, to learn how to build

customized models with TensorFlow. Your knowledge of TensorFlow Core will

help you understand and debug your own models.

If you want to learn more about the inner workings of TensorFlow consider the

following documents, which go into more depth on many of the topics discussed

here:

* @{$graphs}

* @{$tensors}

* @{$variables}

|